Most people are aware that asking a question can reveal ignorance, and out of fear avoid doing so in public, thus frequently remaining ignorant. They are not entirely wrong: by revealing exactly what they do not understand they allow other to make estimates of their intelligence. Hence the benefits of looking up things in private, on the internet.

I am a fan of everywhere, everytime, universal IQ tests: these are based on the notion that life is an intelligence test, and that estimates of ability can be drawn from all behaviours, even incomplete snippets of behaviour. I am on the lookout for research showing that IQ can be estimated from non-IQ test real world activities, of which asking questions is one.

The power of Google was first brought home to me by a little vignette. About 7 years ago I had gone to a vast warehouse called PC World, in an attempt to clear up some problems on a computer. They quoted me a price higher than the value of the actual device, but after I had remonstrated with them, told me in a whisper that there was a little place up the road which would do the job for half the price.

The small shop was sparse: a front room with some printers and a few laptops for sale, a back room for technical staff. The boss was an English countryman who presided over all with a kindly humour, dressed as if going out with his dogs; the technical assistant was a young Sikh with a warm but weary smile who confided to me, as he worked on my computer, that he had told the boss a hundred times that the “print a page for 20 pence and help locals with software” service was totally uneconomic and a real nuisance. Our consultation was interrupted by the hesitant entrance of a very short and frail old lady, unsteadily carrying a very large laptop. Once she got to the counter she lifted it up with some difficulty, glared at him; and said in accusing tone of voice: “I’ve lost my Google”.

Presumably there is a difference between googling: “How do I extend my penis” and “Does Hilary Mantel know any history?” Can that difference provide IQ estimates? Equally, can you distinguish between: “Thuggish”, “Ruggish”, “lamium” and “liatris”, and do any of these have predictive value?

McDaniel, Pesta and Gabriel (2015) Big data and the well-being nexus: Tracking Google search activity by state IQ. Intelligence 50 (2015) 21–29

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B3c4TxciNeJZRjFrOElKSHdjZ0k/view?usp=sharing

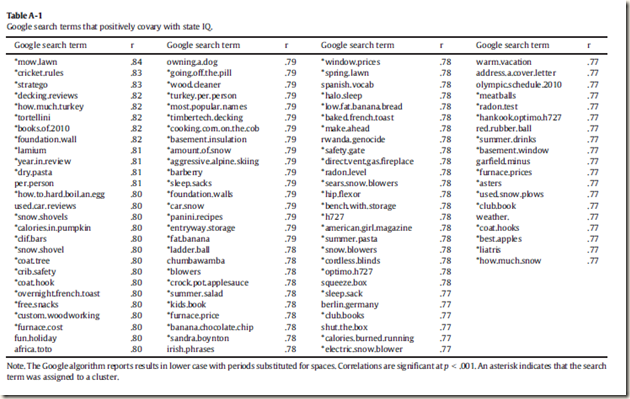

The McDaniel team have dipped their fingers into the American soul by linking US State level google searches with state scholastic achievement levels to as to find the search items which best reveal intelligence, both high and low. I get the impression they found out much about their fellow citizens which they did not previously know (nor did I).

They used the Google Correlate algorithm (a database tracking billions of user

searches) to identify search terms that co-varied most strongly with U.S. state-level IQ and wellbeing. First, they identified the 100 strongest positive and negative search term covariates for state IQ. They then rationally clustered search terms into

composites based on similarity of concept, and correlated those composite scores with other well-being variables (e.g., crime, health). Search-term composite scores correlated strongly with all well-being variables.

We used state well-being data from Pesta et al. (2010), who created six sub-domains of global well-being: IQ, religiosity, crime, education, health, and income. IQ was estimated from public school achievement test scores (see McDaniel, 2006). Religiosity was derived from state-level survey data assessing fundamentalist religious beliefs (e.g., “My holy book is literally true;” “Mine is the one true faith”). Crime was created from various violence statistics, including burglary, murder, rape, violent crimes, and the number of inmates per capita. Education included the percentage of residents with (a) college degrees and (b) jobs in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics. Health included infant mortality and the incidence of obesity, smoking, and heart disease. Finally, income included income per capita,

disposable income per capita, percent of families in poverty, and percent of individuals in poverty.

McDaniel had already calculated estimates of IQ for the 50 US states. The authors note: Aggregate IQ measures correlate strongly with many other meaningful variables. Examples include aggregate IQ predicting levels of institutional quality

(Jones & Potrafke, 2014), absolute latitude/temperature (León & León, 2014; Pesta & Poznanski, 2014), election outcomes (Pesta & McDaniel, 2014), economic freedom (Belasen & Hafer, 2012), religiosity (Reeve, 2009), crime (Templer & Rushton, 2011), education (Pesta et al., 2010), health (Eppig, Fincher, & Thornhill, 2011; Reeve & Basalik, 2010), and income (Lynn & Vanhanen, 2002, 2012). In fact, levels of religiosity, crime, education, health, and income are themselves largely inter-correlated within the 50 U.S. states.

We show that IQ and well-being covary with an activity ubiquitous in many

people's lives—conducting Google searches on the internet. Billions of Google searches are performed per day (Internet Live Stats, 2014). These searches provide snapshots of interesting human behavior. Moreover, many state well-being variables

are derived from self-report data (e.g., religious belief data, census survey data) that may be influenced by impression management and self-deception (Paulhus, 1991), in addition to potentially being affected by accuracy of memory and inattentive

responding. In contrast, the current study employs novel measurement methods (massive archival records of internet searches) that are not affected by typical problems inherent in self-report data. Our data are therefore both unobtrusive and non-reactive.

We report that some specific search terms co-vary in frequency with each state's relative level of IQ and well-being. We make sense of these correlations by using rational clustering, and by referencing extant literature to explain why the derived clusters might fall within the well-being nexus.

Now it is time to skip the methodological details (which these authors and their confederates relish) and peer ahead at the actual results. In Table A - 1 are the terms which show a positive relationship with intelligence. For the life of me I cannot understand why “mowing lawn” or “cricket rules” top the list. At least the 9th ranked search “lamium” is Latin, but what sort of intellect requires guidance on the boiling of an egg? We are talking State averages, I know, but these searches are a revelation to me.

Now we turn to searches which are associated with more modest intellects. I find these more cheerful, and somewhat more predicable. Eye-shadow tutorials indeed. Before long there will be Masters courses in the topic. Kitty shoes, clothes, and stuff is very interesting. You may already know this, but a Kitty shoe is like an ordinary shoe, but with “Hello Kitty” and a drawing of a kitty on it. To save you searching for it, I have copied it below. Sweet.

By now you will be asking yourself what “asvab” stands for: Armed Forces Vocational Aptitude Battery. Very sadly, wanting to read a simple guide as to how to do this test is not associated with high aptitude. However, it does show that the armed forces have learned about the importance of IQ the hard way, and have been given carte blanche to use IQ tests to reject as many candidates as fail to reach their standards.

I find this paper highly instructive. The authors have opened a new window on the mind. They would like to go beyond the 100 terms, and should be encouraged to do so when the data become available. With a bit of help from them I will be able to make significant additions to my “7 tribes of intellect” post.

As to Hilary Mantel, the Wiki entry on Thomas Cromwell is a good place to start, and gives the major biographies. On a final point, I wish to make it absolutely clear that when I google “basic statistics for dummies” I am merely idly checking whether the procedures are being described with absolute accuracy. And a Goodbye Kitty to all of you.