Dear Kim,

Thanks very much for coming back to me with your comments. Despite my friendly entreaty to all authors to respond to my postings, many choose silence, so it is great to be able to debate with you. I do not have a “Psychological Comments” T-shirt or coffee mug to offer you (and doubt they would be considered highly motivating) but I appreciate your response.

We agree that it is worth looking at data sets which have interesting or unique aspects (in this case brain scans) despite them not being fully representative of the general population. Wherever the characteristic in question is rare we are justified in digging up every possible data set, and making Bayesian approximations to obtain the best available estimate of the variable in question.

However, where very big issues like social class, social mobility, income, wealth, health, and scholastic achievement are concerned, representativeness is crucial. Epidemiological samples rule. For example, the Dunedin sample shows that most social problems, and subsequent costs of remediation, are due to a small number of children. As I mentioned in my post on your paper, Moffitt and Caspi show how one might misunderstand child development in general just by missing a small number of difficult children, who are of course those least likely to volunteer for a health checkups, let alone brain scans.

http://drjamesthompson.blogspot.co.uk/2014/12/are-you-nuisance.html

I think we agree on that anyway, but we may differ on the implications, particularly when it comes to your intervention study, which I will discuss later.

Now to our main points of disagreement, which is that the results you report could be due to genetic factors, whether or not those have been measured in the study.

Correcting for race differences in your sample does not correct for the overall heritability of intelligence and the heritability of other characteristics like brain size in your study children. You corrected for race differences and showed that the income and education correlations with brain surface were not driven purely by racial group differences. (There seems to be a big difference due to African ancestry, but that does not explain all the SES effect). However, that still leaves wide open the obvious explanation, that what you are recording with your scanners are inherited differences that run through the entire sample. I said in my note: SES and brain size can have the same relationship in all racial groups, and yet still be driven by inherited intelligence.

Do you agree that point, or not? My objection was that you appeared to think you had covered the overall heritability confounder with your racial group correction, and you haven’t. To illustrate the point, imagine you restrict your analysis to the European children and find that income and education are correlated with brain surface. That association could be due to the common factor of genetics. Bright parents have brighter children (on average) and also command higher salaries (though their resultant wealth probably doesn’t give much of a boost to the school attainments of their children). Even if you don’t have genetic data in your particular study, the many publications on the heritability of intelligence mean that it is very likely that your results are driven by inherited characteristics, and these can’t be ignored simply because genetic effects have not been measured in your particular study. For example, this recent study finds “Genetic influence on family socioeconomic status and children's intelligence” from purely genetic analyses.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160289613001682

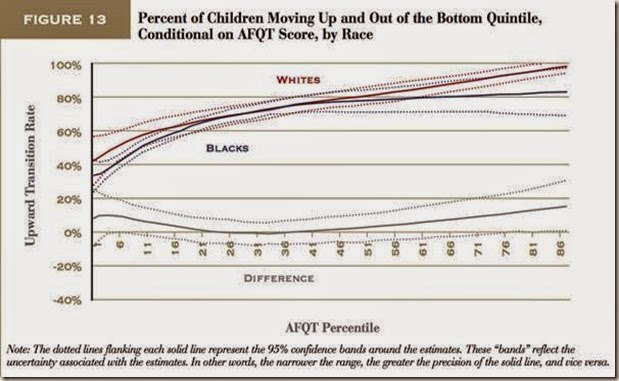

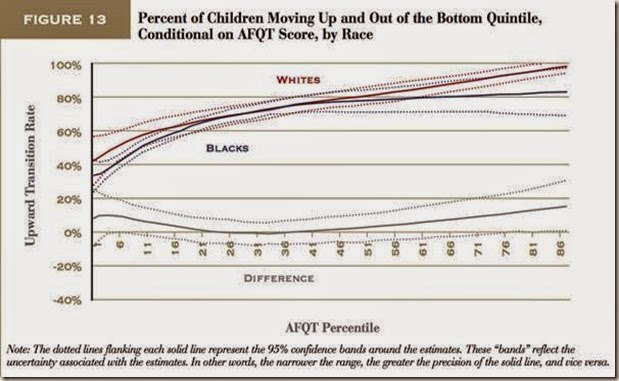

It was for that reason that I argued it would have been better to have collected more data on the parents. (This could include scans of parental brains, but testing ability would be more cost effective). Having parental intelligence scores would have allowed you to compare the predictive power of three variables: income, education and parental intelligence. (Or if that hadn’t been done by the PING study, at least it would have allowed you to explain how such data would have helped you identify possible causes). Those three variables of income, education and intelligence are enough to begin to sketch out putative causes, particularly when considered over generations. For example, the Pew Trust has looked at social mobility in the US and finds that IQ is a much stronger predictor than race for escaping the bottom quintile of income (Pew Trust report; NLSY again, AFQT=IQ scores). If you are bright you rise.

http://infoproc.blogspot.co.uk/2015/04/income-weath-and-iq.html

Now we come to what I consider the crunch. Here are your comments: One thing in your commentary I find unclear. You state that we “could have given the parents the psychometric test battery for good comparability.” However, parent cognitive ability is, of course, itself influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, so it is not clear to me how this would have disambiguated this question of causality. Both cognitive ability and socioeconomic status have significant heritable and environmental components, and our study was not designed to address the question of their relative balance. Parent-child genes are correlated, but so are parent-child environments. Incidentally, scanning the parents would not solve the problem either, as parental brain morphometry would be both genetically and environmentally influenced, as well.

I think is worth expanding upon this point. Your study may not have been designed to address the question of the relative balance and power of parental cognitive ability and socioeconomic status, but I was suggesting a quick way beginning to repair that omission. By measuring parental status and parental intelligence we can compare the power of these two predictor variables. I mentioned the Nettle (2003) paper in my original posting. Regarding my suggestion that the parents be given the adult version of the test battery taken by the children you said (above) “parent cognitive ability is, of course, itself influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, so it is not clear to me how this would have disambiguated this question of causality.”

What Nettle did was to show, on an excellent epidemiological sample and a long follow up, that childhood intelligence at age 11 was a better predictor of social mobility than social class of origin. For the class-based sociological hypothesis regarding life outcomes that is an awkward finding. It suggests that something which is not under direct social control (intelligence) is having a bigger effect than something which, in sociological theory, is almost entirely under social control (allocation to class). That is why I say you need to test the abilities of parents, not just their incomes or years of education. There is a quick summary of why heritability applies to cognitive neuroscience by Deary and Plomin (2014) http://drjamesthompson.blogspot.co.uk/2014/12/five-gold-rings-inherited.html

Davies et al. (2015) is a good example of current work on the genetics of intelligence.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B3c4TxciNeJZUjdEVHF4dkVtaTQ/view?usp=sharing

As opposed to the genetics plus environment position, the dominant position in much of contemporary psychology seems to be the sociological argument, which gives precedence to social class, income, wealth and power. The argument goes thus: class strongly influences living circumstances; those living circumstances determine most social outcomes; class casts some people into poverty, poverty stunts intellectual development, lower intelligence is a downstream effect of class-based poverty, so the best way of dealing with low ability is to increase income.

If this sociological hypothesis were correct, social class of origin would be the best predictor of later achievement, and other measures influenced by class would be somewhat weaker predictors. They would trail in the wake of social status.

To use a ballistic analogy: if the higher status, income and wealth of parents are like a big Howitzer which fires their children much longer distances so that they land further up the social hierarchy, then the intelligence of those children is mainly a downstream effect of wealth, and is of lesser significance predictive significance. If poverty per se is so impactful on the developing brain, class of origin will strongly influence everything about the child, including their intelligence.

As far as I can see, that isn’t so. Even within the same family, brighter children end up earning more than their less bright siblings. This cannot be explained by family wealth and status. Additionally, genetic studies tend to find zero effect for the “shared variance” of family and school, but a big effect by the creation of personal niches, the so-called “non-shared” environmental effect.

It seems that families are more like Katyusha multiple rocket launchers, firing salvoes of rockets less accurately than a Howitzer, with different ranges due to the lack of a gun barrel and variations in the propellant in each rocket, the propellant being, by analogy, individual differences in intelligence.

Anyway, by looking at sociological variables through the generations, and looking at intelligence as well, one can identify their relative power in determining which children will be in each class in the next generation. The composition of classes varies from one generation to the next. Your objection (above) is that every measure is a mixture of genetics and environment, and thus uninformative. Not really. If parental intelligence turns out to be more predictive than social status, that is highly informative. No genetic testing is necessary, though it would be a welcome addition. The possibility that genetics is driving intelligence and consequently social class remains open as a major confounder of your observed income/brain link, even if the particular study design makes it hard to reveal its influence. I doubt you intend to commit the “sociologists’ fallacy” of assuming that by selecting people by income and finding differences it can be suggested that income has been established as a cause of those differences. Reader “Galtonian” in the comments section on your post gives an interesting link to a paper showing high heritabilities for brain surface, which has obvious relevance to your study. Twin studies are informative, and their results have wide application.

http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/content/21/10/2313.full.pdf+html

I think that all these genetic studies should be part of your thinking about your findings. I said that you had “missed a trick”. Just one test result on the parents would have strengthened whatever conclusions you later came to in your paper. You say your study could not disambiguate the question of causality, but in fact your interpretive framework clearly and explicitly favours the environmental over the genetic. I am asking you to consider both, and to make that more apparent in your interpretations of your findings.

In parenthesis I should say that although I can find examples of good studies showing that intelligence measures outperform social class measures, I don’t think there is a meta-analysis of all the published studies. Together with Tim Bates I would like to collect a database of studies which include both social variables and intellectual measures so that we can check whether this finding (of IQ being a better predictor than social circumstances) holds true in all the relevant literature.

My reference to the other studies listed here is not meant to bludgeon you, but to reveal the findings which I rely upon for my arguments. (I do not pretend it is an exhaustive list, merely some exemplars I can recall). Richard Feynman once remarked that psychology differed from physics in that psychologists weren’t particularly bothered with confounders even when publications showed they were present (he gave an example from animal learning which revealed an experimenter artefact). Physicists, on the other hand, stopped what they were researching until they had ironed out the measurement and interpretative imperfections. I know that psychology is different from physics, but his insight made me smile ruefully.

Now a few comments on your upcoming intervention study. Showing any effect experimentally would be great. I expect you will find some effects. However, virtually all intervention studies with developing children throw up positive results in the early stages. By age 17 the effects tend to be smaller or disappear. The follow up will be the test, and you might have to wait 10 years for that, which is the peril of these studies, before saying the intervention was “definitive”. Few interventions achieve that status. The Abecedarian project had to wait 23 years for a full evaluation, and Ramey told us in 2013 that he would be repeating the experiment, and that every child would have brain scans and a full genomic analysis. (I don’t know the state of progress at the moment). I assume, given funding, you will collect genetic samples from both children and parents. If at some stage you can send me the protocol, or just an outline of the experimental set-up, that would be good. I point out that though you say: “Both cognitive ability and socioeconomic status have significant heritable and environmental components, and our study was not designed to address the question of their relative balance” the hypothesis you are about to test in your intervention study is entirely about the environmental component of cash payments to families. I have a suggestion below.

In sum, it seems we are still wide apart on the central issue, which is that the heritability of behaviour and abilities should be a standard part of the interpretation of children’s development, and that more data needs to be collected on the abilities of parents. Even now, in your intervention study pilot, why not give parents and children the WORDSUM test or something like that? It is very quick and pretty crude, but much, much better than nothing. You could see if this measure of parental intelligence helped predict the outcome of your interventions, and whether it did so more powerfully than the usual demographic variables. You would also be able to compare your sample with US SES norms on vocabulary. Given a bit more time, your assessment of parental intelligence could be more detailed, allowing you to compare the predictive power of class and intelligence on a common format.

It is not too late. Don’t hesitate: test the ability of the parents!

Best wishes

James