I have admired Philip Tetlock since, almost 30 years ago, he reviewed a book I had just written which contained one big and so far untested prediction, and gave it by far the most detailed, insightful and helpful assessment it had received among many warm but perfunctory reviews, mildly adding references to a few papers which, when I followed them up, showed me exactly how much I had missed out. His kindness made his critical points far more effective. (In a subsequent lecture tour I met up with one of the international affairs experts he had mentioned, who offered to work with me, though in the end I went on to other things, and consequently made no revision of the book).

Tetlock, P.E. (1986). Review of J. Thompson, Psychological aspects of nuclear war. British Journal of Social Psychology, 25, 78-79.

Now the Press are picking up his work on super-forecasting, which has major implications for how we go about anticipating and planning for future events, supposedly one of the features of high intelligence. Bright people should be particularly good at forecasting, shouldn’t they?

Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction. Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner. Sep 29, 2015

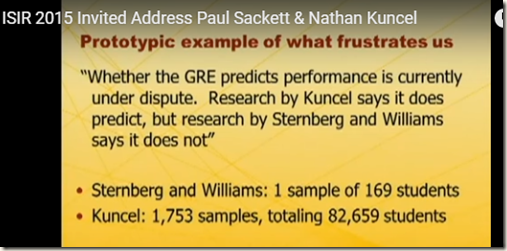

What has Tetlock found? First, that most pundit forecasts are unfalsifiable. Even time travel would not help you know if the predictions of these commentators had been met. They are at the low level of Nostradamus and contemporary journalism. Second, if you run a proper forecasting contest (not “will there be a stock market correction sometime soon” but “what will the Standard and Poor index stand at on 31 December 2015”) most commentators are “too busy” to participate. They do the broad brush stuff which gets well paid, not the nitty-gritty testable stuff that nerds do for fun.

In his 1953 essay on Tolstoy’s view of history, Isaiah Berlin drew a distinction which he intended to be no more than an intellectual game, though he later admitted that every classification throws light on something.

There is a line among the fragments of the Greek poet Archilochus which says: ‘The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.’ Scholars have differed about the correct interpretation of these dark words, which may mean no more than that the fox, for all his cunning, is defeated by the hedgehog’s one defence. But, taken figuratively, the words can be made to yield a sense in which they mark one of the deepest differences which divide writers and thinkers, and, it may be, human beings in general. For there exists a great chasm between those, on one side, who relate everything to a single central vision, one system, less or more coherent or articulate, in terms of which they understand, think and feel – a single, universal, organising principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance – and, on the other side, those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way, for some psychological or physiological cause, related to no moral or aesthetic principle. These last lead lives, perform acts and entertain ideas that are centrifugal rather than centripetal; their thought is scattered or diffused, moving on many levels, seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects for what they are in themselves, without, consciously or unconsciously, seeking to fit them into, or exclude them from, any one unchanging, all-embracing, sometimes self-contradictory and incomplete, at times fanatical, unitary inner vision. The first kind of intellectual and artistic personality belongs to the hedgehogs, the second to the foxes; and without insisting on a rigid classification, we may, without too much fear of contradiction, say that, in this sense, Dante belongs to the first category, Shakespeare to the second; Plato, Lucretius, Pascal, Hegel, Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Ibsen, Proust are, in varying degrees, hedgehogs; Herodotus, Aristotle, Montaigne, Erasmus, Molière, Goethe, Pushkin, Balzac, Joyce are foxes.

(As you can see, Isaiah Berlin could write. He was also very kind, and a friend tells me stories about him, while pointing at the two prints Berlin gave him).

Tetlock has taken this distinction to heart as a classificatory system. Forecasters can have a specialist, narrow focus expertise (hedgehogs) or a broad overview, using plagiaristic combinations of other people’s deep knowledge plus their own feelings (foxes).

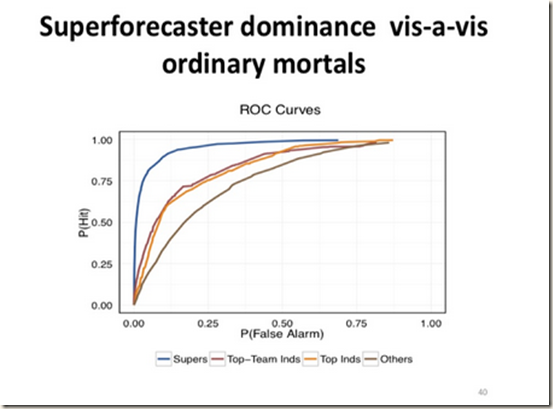

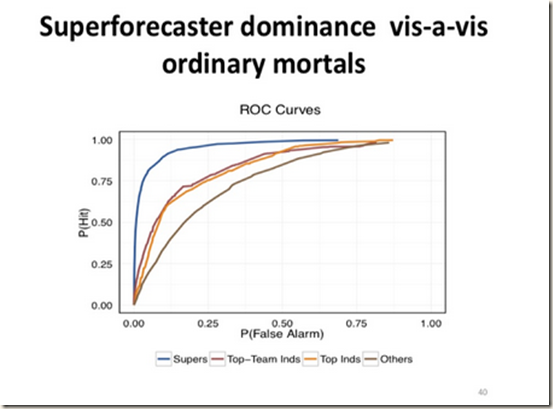

After conducting many prediction contests, Tetlock finds that some people are particularly accurate, and deserve the accolade of being superforecasters. Superforecasters could assign probabilities 400 days out (before the event) about as well as regular people could about eighty days out. Many of the superforecasters were quite public-spirited software engineers. Software engineers are quite over-represented among super-forecasters.

A surprisingly large percentage of our top performers do not come from social science backgrounds. They come from physical science, biological science, software. Software is quite overrepresented among our top performers. If you looked at the personality profile of super-forecasters and super-crossword puzzle players and various other gaming people, you would find some similarities.

The individual difference variables are continuous and they apply throughout the forecasting population. The higher you score on Raven’s matrixes the higher you score on active open-mindedness, the more interested you are in becoming granular, and the more you view forecasting as a skill that can be cultivated and is worth cultivating and devoting time to, those things drive performance across the spectrum, and whether you make the super-forecaster cut, which is rather arbitrary or not. There is a spirit of playfulness that is at work here. You don’t get that kind of effort from serious professionals for a $250 Amazon gift card. You get that kind of engagement because they’re intrinsically motivated; they’re curious about how far they can push this.

Comment: I think this makes sense. These super-forecasters are probably counters, not chatterers, that is, STEM not Verbal, with high fluid intelligence. Software has to work, and there are many, many ways in which it can go wrong. Murphy’s Law applies. Programs have to be tested to flush out errors, and you have to simulate the special situations users will create which can make an untested system crash. This background makes software engineers cautious, humble, and supremely focussed on “on budget, on time”.

Tetlock tried to boost forecasting accuracy by means of his Good Judgment Project, and found that his training techniques could boost accuracy by 50-70% from the group average. The project does this in the following ways:

The test of fluid intelligence was Raven’s Matrices. I promise you I began writing this post without knowing that. What I thought would be a little break from intelligence research turns out to prove the adage that intelligence runs through human life like carbon through biology.

You may have heard about the wisdom of crowds. I am with Dryden (1668) when he said: If by the people you understand the multitude, the hoi polloi, tis no matter what they think, they are sometimes in the right, sometimes in the wrong; their judgment is a mere lottery. As a general rule, crowds are in favour of war at the beginning of wars, and against them if they drag on, which most of them do.

So, the wisdom of crowds depends on the intelligence of the crowds, or more precisely, it is boosted by paying extra attention to intelligent crowd members. Where opinions are polarised, then one option is to use an algorithm to combat the centralising and emasculating effect of those clashing perspectives. This helps get useful predictions out of crowds, but does not help super-forecasters (who probably know how to combine conflicting opinions anyway).

An example of Kahneman based predictive training is this rule of thumb: The likelihood of a subset should not be greater than the likelihood of the set from which the subset has been derived.

What we’re trying to encourage in training is not only getting people to monitor their thought processes, but to listen to themselves think about how they think. That sounds dangerously like an infinite regress into nowhere, but the capacity to listen to yourself, talk to yourself, and decide whether you like what you’re hearing is very useful. It’s not something you can sustain neurologically for very long. It’s a fleeting achievement of consciousness, but it’s a valuable one and it’s relevant to super-forecasting.

The beauty of forecasting tournaments is that they’re pure accuracy games that impose an unusual monastic discipline on how people go about making probability estimates of the possible consequences of policy options. It’s a way of reducing escape clauses for the debaters, as well as reducing motivated reasoning room for the audience.

Regarding partisan pundits, Tetlock says:

High stakes partisans want to simplify an otherwise intolerably complicated world. They use attribute substitution a lot. They take hard questions and replace them with easy ones and they act as if the answers to the easy ones are answers to the hard ones. That is a very general tendency.

Does my side know the answer? is the really hard question. The easier one is, whom do I trust more to know the answer, my side or their side? I trust my side more to know the answer. Attribute substitution is a profound idea, and it allows us to think we know a lot of things that we don’t know. The net result of attribute substitution among both debaters and audiences is it makes it very hard to learn lessons from history that we weren’t already ideologically predisposed to learn because history hinges on counterfactuals

Tetlock is now focussing on the societal impact of his findings, hoping to improve the predictions on which decisions are based. The minimalist goal is to make it marginally more embarrassing to be incorrigibly close-minded, just marginally. The more ambitious goal is to make it substantially more embarrassing, and that requires talent and resources of the sort that academics like myself don’t possess. I don’t know how to create a TV show.

Tetlock has some advice for improving forecasts. Like most advice it has some disappointments, in that a researcher close to the material understands in detail what is meant by “strike the right balance” but the phrase itself is of little help, simply an irritating truism.

Ten Commandments for Aspiring Super-Forecasters

1 Triage. Concentrate on questions which lie in the Goldilocks Zone between Clocklike predictable and Cloudlike impossible.

2 Break seemingly intractable problems into tractable sub-problems. How many potential mates will a man find in London? Divide the total population by half to get the number who are women, then by those in his age range, those who are single, those of roughly the right age, those with a university degree, those who he will find attractive, those who will find him attractive, those who will be compatible and you end up with 26 women out of a population of 6 million.

3 Strike the right balance between inside and outside views. How often do things of this sort happen in situations of this sort? When estimating the time taken to complete a project, take the employee estimate with a pinch of salt, and the client estimate as a correction factor.

4 Strike the right balance between over-reacting and under-reacting to evidence. The best forecasters tend to be incremental belief updaters, slightly altering probability estimates. They also know when to jump fast.

5 Look for clashing causal forces in each problem. Understand both thesis and antithesis, summarize both so you recognise how they will develop, then attempt synthesis.

6 Strive to distinguish as many degrees of doubt as the problem permits but no more.

7 Strike the right balance between under- and overconfidence, between prudence and decisiveness.

8 Look for the errors behind your mistakes but beware of rearview mirror hindsight biases.

9 Bring out the best in others and let others bring out the best in you.

10 Master the error-balancing bicycle.

To get further into this, either read the book or look at his Edge masterclass (5 parts) in which he answers question and responds to suggestions.

http://edge.org/edge-master-class-2015-philip-tetlock-a-short-course-in-superforecasting

Comment

This is a first look at an engaging and important problem: how to perceive the world accurately enough to work out what will happen next. Intelligent beings need to be accurate much of the time. If Alex Wissner-Gross (2013) is right, intelligence is a thermodynamic process, and can spontaneously emerge from any organism’s attempt to maximise freedom of action in the future. The key ingredient seems to be the maximisation of future histories.

The key to decision making is to keep one’s options open, the most important option being staying alive.