Things move fast. A published paper comes to the attention of Steve Sailer and suddenly a section of a puzzle gets completed.

http://www.unz.com/isteve/school-test-scores-in-africa/

Better still, the boundaries of ignorance get pushed backwards, which is always a good idea, and a fine Christmas present.

From the isolation of my study, and from the depths of my ignorance, I had always bemoaned the fact that poorer countries, particularly in Africa, avoided taking part in PISA and similar international assessments. The suspicion was that they were avoiding getting bad results, which would redound on their national pride, showing them to be dull and/or incapable of organising their schools properly. PISA has the capacity to spread embarrassment far and wide, in rich as well as poor countries, and I am all in favour of that. Let the over-paid educational authorities of the rich world be confounded by the wit of poorer nations, and may their cosy empires fall. Also, may badly organized countries stop blaming poverty and make sure they pay and support their teachers.

The problem with the lack of participation of these countries was that researchers lost a possible confirmation or disconfirmation of the IQ results obtained on those countries, which in the case of Africa seem to be too low to be believed. How to sort out this problem?

Justin Sandefur, Working Paper 444, December 2016, Center for Global Development.

Internationally Comparable Mathematics Scores for Fourteen African Countries

Abstract

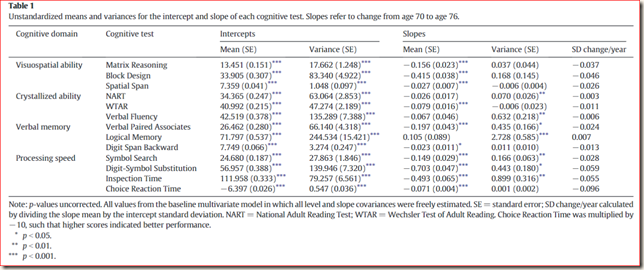

Internationally comparable test scores play a central role in both research and policy debates on education. However, the main international testing regimes, such as PISA, TIMSS, or PIRLS, include very few low-income countries. For instance, most countries in Southern and Eastern Africa have opted instead for a regional assessment known as SACMEQ. This paper exploits an overlap between the SACMEQ and TIMSS tests—in both country coverage, and questions asked— to assesses the feasibility of constructing global learning metrics by equating regional and international scales. I compare three different equating methods and find that learning levels in this sample of African countries are consistently (a) low in absolute terms, with average pupils scoring below the fifth percentile for most developed economies; (b) significantly lower than predicted by African per capita GDP levels; and (c) converging slowly, if at all, to the rest of the world during the 2000s. While these broad patterns are robust, average performance in individual countries is quite sensitive to the method chosen to link scores. Creating test scores which are truly internationally comparable would be a global public good, requiring more concerted effort at the design stage.

http://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/math-scores-fourteen-african-countries0.pdf

This fine paper comes from the economic sphere of study, so does not reference much psychometric literature. A pity, because it contributes much to the debate on group differences. Economists often ignore the concept of intelligence. Sandefur also seems to accept African national economic statistics, though he probably realizes they are prone to wishful thinking. The author is circumspect about the key issue of comparability of difficulty levels across tests, but seems to have made reasonable choices. I doubt that a re-working would change the picture very much.

The linkage is made possible by Botswana and South Africa having taken both the regional SACMEQ and the TIMSS international tests; and the 2000 and 2007 regional tests having used some of the TIMSS international test questions.

Whatever the linkage methods, the results are pretty grim:

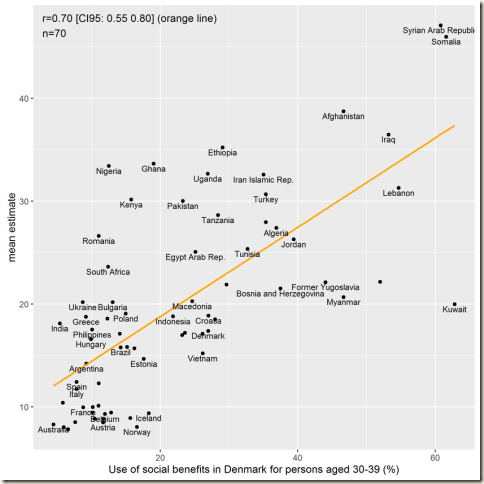

Substantively, the results here are daunting for African education systems. Most of the national test-score averages I estimate for the thirteen African countries in my sample fall more than two standard deviations below the TIMSS average, which places them below the 5th percentile in most European, North American, and East Asian countries. In contrast, scores from the SACMEQ test administered to math teachers are much higher, but fall only modestly above the TIMSS sample average for seventh- and eighth-grade pupils, in line with earlier analysis by Spaull and van der Berg (2013). African test scores appear low relative to national GDP levels; in a regression of average scores on per capita GDP in PPP terms, average scores in the SACMEQ sample are significantly below the predicted value using all three linking methodologies. Furthermore, there is little sign that African scores were improving rapidly or converging to OECD levels during the 2000s.

Of course, readers of this blog will know that Richard Lynn’s personal collection of international intelligence test results, now in the Becker edition, puts Sub Saharan intelligence two standard deviations below the European mean, so it closely matches these results.

https://drjamesthompson.blogspot.co.uk/2016/10/richard-lynn-intelligence-database.html

The advantage of using Maths tests as a proxy for intelligence tests is that most intelligence tests have an Arithmetic subtest and/or number series tests, so one can follow some known correlations to estimate comparability's. Better still, Maths has a logic to it, so it is valid to talk about some operations being more complex than others. The same item is very much the same item whichever test you find it in, because the same steps are required to solve it. It has the cold beauty of which Bertrand Russell spoke:

“Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty — a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show. The true spirit of delight, the exaltation, the sense of being more than Man, which is the touchstone of the highest excellence, is to be found in mathematics as surely as poetry”.

More prosaically, maths opens the door to many other intellectual tasks, much as literacy supersedes the oral tradition.

What is to be done with African Maths teachers? Heiner Rindermann, trying to resolve the debate between Richard Lynn and Jelte Wicherts, put Sub-Saharan African IQ at 76. As to African Maths teachers’ results in this paper, he says: In some African countries teachers seem to have lower abilities than students in Europe or East-Asia!

If teachers are one standard deviation above the national mean, then they would have IQs of 91, if two standard deviations above the mean still only 106. This is not a level likely to inculcate in their students a passion for Maths, a subject which every schoolchild recognizes as being different conceptually from other language based subjects, and hard to master. What makes problems difficult? I digress.

Convergence is a much desired trajectory where racial differences are concerned. Put in the educational resources and the slower countries will catch up with the faster ones. Makes sense. However, this sought-after outcome does not always materialize. Convergence will take place sometime between 40 years and never, according to Woodley and Meisenberg.

https://drjamesthompson.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/original-paper-are-cognitive.html

Turning to the pressing issue of how to raise scholastic attainments, it is unlikely to be a simple question of investing money. Saudi Arabia has had plenty of money to spend on education for almost 50 years, and just look where it languishes in the table, in the company of far less wealthy Swaziland, Tanzania, Botswana and Uganda. Of course, given Saudi Arabia’s mean IQ of 78 that would be entirely as expected. No Africanist, I have nonetheless sung the praises of Botswana, a well run country which invests heavily in education (the Diamond Generation). Despite that, Botswana is not getting much bang for its buck. If Botswana cannot converge on other nations, despite having done so many things right, that should give pause for thought. Botswana’s mean IQ 73.

https://drjamesthompson.blogspot.co.uk/2013/12/the-wages-of-mandela.html

A summary of investment in education suggests that the pay-off is front-end loaded: the first $5000 has a big effect, and then it tends to plateau thereafter. Another way of looking at it is to note that once countries get to $16,000 GDP per capita then schooling in those countries accounts for only 10% of the variance of student attainment. So, poor countries (most of Africa is well below this level) should have plenty of scope for educational gains.

This paper completes a jigsaw puzzle, and extends the global scholastic attainment dataset by 14 countries. It confirms the Lynn assessments as likely to be correct, within a measurement error of roughly 4 IQ points. For these countries at least, it gives no hint of exceptional talents beyond that expected on the basis of intelligence testing.

I don’t do policy, so this is said more in hope than with any expectation of a good result, but if young Europeans school-leavers with good maths qualifications intending to do good works in Africa want to be most effective, instead of digging ditches they should concentrate on teaching Maths.