A book has just been published in memory of Phil Rushton, drawn from contributions to the special issue of Personality and Individual Differences in his honour, which became an obituary after his untimely death of Addison’s disease in 2012.

“The Life History approach to Human Differences” Ed Helmuth Nyborg, Ulster Institute for Social Research, 2015. www.ulsterinstitute.org will provide the eBook version for £5.

The book gathers together one of the final interviews Phil gave, and a subsequent obituary, both by Helmuth Nyborg; substantive contribution from Arthur Jensen on mental ability, Linda Gottfredson on race research, Jan te Nijenhuis on Flynn effect and g, Heiner Rinderman on African ability, Paul Irwing on general factor of personality, Donald Templar on personality theory, Yoon-Mi Hur on altruism, AJ Figueredo, Tomas Cabeza de Baca and Michael Woodley on Life History, Richard Lynn on r-K history, Helmuth Nyborg on migration, Gerhard Meisenberg and Michael Woodley on global behaviour variation and the same two authors on dysgenic fertility.

All this for two cups of coffee (at London prices).

For those of you who don’t drink coffee, here is a brief note, never published, which I put together in 2012 describing Phil Rushton’s work on intelligence and personality. At 1862 words it follows my usual stricture that explanations should be given in fewer than 2000 words. It is written in the present tense.

Phil Rushton is tough minded, and has needed to be. Scholarly enquiry often leads to surprising answers, and expounding unpopular views is no project for the faint hearted. His key achievement has been to gather together what would otherwise have been a rag tag of disparate findings and bind them into a coherent pattern of r-K evolutionary strategies. His approach is one more example of an Eysenkian gesamtkunstwerk, to which those of heriditarian persuasion seem drawn, in which an over-arching theory provides a sweet symphony that brings order to chaos. This has given the debate about behavioural differences between genetic groups a new rationale, and for that alone Rushton deserves praise.

In terms of his approach to the data he has shown doggedness in tracking down evidence and arguing his case. His 2005 review with Jensen sets out the hereditarian case as thoroughly and forcefully as has ever been achieved, and must be considered his shared magnum opus. In the best sense of the term he has been Jensen’s bulldog, taking on all comers with dogged persistence. Jensen and Rushton were able to draw together the main points of a complex argument and also retain the sense of challenge and flexibility as they invited their critics to grasp the gauntlet they had thrown down. By proposing to identify the 10 major fields of contention, and by rating their own progress in each of them they challenged others to reply.

At a time when his critics were denouncing his findings because of what they saw as unrealistically low scores in sub-Saharan Africans, Rushton was in fact arguing, on the basis of item analyses, that it was likely that all human beings shared a universal problem solving process. His very detailed studies of disparate racial and cultural groups showed that there were very few anomalies which required special explanation. The parsimonious explanation was that people do not differ in type when confronting intellectual puzzles, though they often differ in power. Interestingly, many of the criticisms of the low scores obtained in Africa revolved round the suggestion that Western tests did an injustice to African thought processes. Critics implied that there was an African way of thinking and of solving problems, and that special tests were required to reveal this potential. In modern parlance, Africans were conceived of as using a different computer operating system, which could not be fairly evaluated if one tested it with the wrong file format. However, there was never any detailed exposition as to what this African way of thinking consisted of, nor whether such continent-specific mental processes would be desirable. Real world observation shows that Africans use modern technology, understand Western culture and excel at Western games, despite these having Western rules and practices. In practical terms there seems to be no parallel universe of African thought. Reassuringly, Rushton’s detailed investigations in South Africa and in other parts of the world found no differences in kind, though differences in degree remain, and are important. So, one was left with a pleasing paradox. Rushton, excoriated by critics, has shown that humans are very alike and have a universal thought process as regards essential problem solving, though they differ in power, while the critical attack on him had implied that Africans were different in some profound cognitive way, which turns out to be false. Interestingly, defences mounted to argue against the observation of racial differences in intellect are often worse than the observations themselves. Differences in intellectual power can be due to mutable effects, whereas the suggestion that one thinks profoundly differently because of one’s culture or genetics, such that one is a different type, seems less mutable.

Among psychology researchers there has been general agreement that personality is best described by “The Big Five” dimensions (Neuroticism, Extraverstion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness). Rushton considered whether it would be possible to reduce these 5 to 1 general factor. High scores on this General Factor of Personality indicate a “good” personality; low scores a “difficult” personality (someone who is hard to get along with). Individuals high on the General Factor of Personality are altruistic, agreeable, relaxed, conscientious, sociable, and open-minded, with high levels of well-being and self-esteem. Those with poorer personalities are at the other end of the descriptive spectrum. They would tend to be selfish, disagreeable, anxious, not dependable, unsociable, closed-minded or rigid thinkers, with high levels of distress and low self-esteem.

Rushton’s proposed general factor of personality (Rushton and Irving, 2011) has many attractive features, not least that it accords with everyday experience. Some people are hard to get on with, and there is often general agreement about this, particularly among employers, who are apt to describe them as “high maintenance”. Personality testing almost always begins with a lie: “There are no right or wrong answers”. It takes a tough minded person to reply “Why not?” There should be right and wrong answers because every day experience shows that some people are very difficult to get along with. Troublesome personalities exist, and extract a heavy cost on other people, most notably when their behaviour is criminal. In the tender minded perspective “it takes all sorts to make a world”. From that tender perspective all personalities are seen as equally valuable, against some unspecified criterion in which all personality types might conceivably be useful in some circumstances. From the tough minded perspective some personalities contribute and others detract. Maintenance costs are borne by others, and this becomes obvious in small companies but is diluted in society at large. The general factor of personality is far more functional, and better grounded in social observation. Measured against the usual social criterion of productive cooperation, some personalities may be considered failures, a others more successful. So, to encapsulate his insight into a revision of the usual platitude about all sorts being required, the riposte is: “it takes the best sorts to make a better world”.

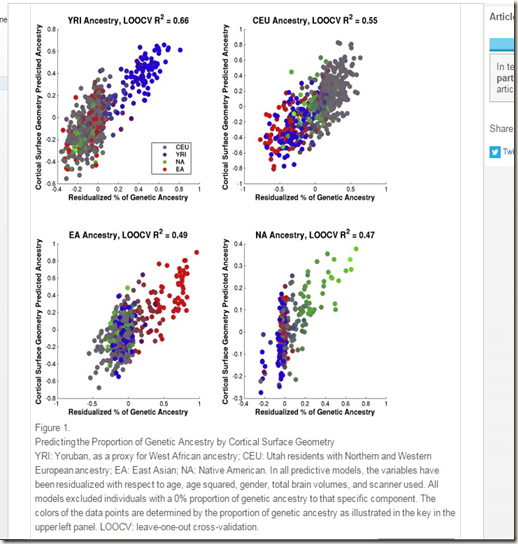

One of the least well known of Rushton’s achievements is to have made a scholarly refutation of Stephen Jay Gould’s attack on the correlation of head size and intelligence. Joining others who had defended Morton and other early researchers, Rushton went further by sending Gould modern data from MRI studies substantiating the cortical size/intellect link, which Gould did not chose to acknowledge in later editions of his work. To those who have bothered to follow the exchange, it was clear that bulldog Rushton had won the tussle. Nonetheless, it remains a social fact that more people have read and remembered the beguiling prose of Gould’s “The mis-measure of man” than have noted Rushton’s scholarly refutation, a clear case of the mis-measure of reputation. This is yet another instance when access to the wider public has been denied to a radical thinker, and views which better fit the zeitgeist get credulous publicity.

Rushton has been able to respond to strong criticism by detailed refutations, and has been at his best when seeking to answer his critics and finding new supportive data. For example, rather than accept the low African IQs he deliberately set out to measure them again in more favourable circumstances. His work in Africa with local psychologists is illuminating because he worked hard to ensure that testing was done properly, and that impediments to good performance were removed. Also, his selection of university students for extra analysis has the merit of plotting out the bell curve, and deriving the underlying population means by inference from intellectually elite groups. This shows his capacity to think through the implications of individual findings, and grasp the big picture. It imposes an inherent reality-check on scores obtained from convenience samples, and allows not only comparisons of population means but also comparisons of elites. At heart, Rushton is willing to test out the implications of findings, and not accept them at face value.

Another example of a willingness to search for links is Rushton’s work on cousin marriage, in which the depression of subtest scores in cousin marriage is linked to racial differences on subtests. Using the method of correlated vectors, he was able to show that two culturally very different groups, African Americans and Japanese children of cousin marriages had something in common: depressed intelligence with some similarity of sub-test patterns, strengthening the case for a genetic component in both. Both the scope and the methods are of interest here.

Rushton has not recoiled from writing popular summaries of his work, doing all he can to disseminate his findings and his theorising. These have taken his views to a wider audience, all the more necessary when it is hard to get past reviewers with strong pre-conceptions as to what the results should look like.

Popularisation involves compromises, and his summaries of r-k life history tables mostly lack specific data. The mere repeating of general phrases such as “higher” or “greater” in the comparison columns is understandable, but potentially weakens the presentation of his case. It gives a general picture to the interested reader, but is too general to satisfy a sceptical critic.

On head circumference and cortical volume Rushton has been a redoubtable debater, and again his capacity to gather and integrate disparate data sources constitutes an incremental meta-analysis, showing the general finding and making a strong case.

His work on Raven Matrices, creating item-by-item heritability and “environmentality” estimates is subtle and initially slightly hard to grasp, but it provides a powerful analytic tool. By looking at each item in terms of heritability estimates derived from twin studies Rushton was able to use these as trace elements which he then followed through disparate samples, showing that a very broad range of cultural background did not generate any conspicuous differences in problem solving strategies. On the contrary, the individual items argue for a universal thought process, at least as far as higher mental functions are concerned.

What is most notable about Rushton is his intellectual resilience. He can grasp the big picture, and can assemble evidence in its favour. He has the capacity to understand the implications of individual findings, and to track down confirmatory or dis-confirmatory consequences. He can also link together entirely disparate publication networks, such as looking at cousin marriage in Japan to illuminate group differences in America. At every stage of discovery he believes he has done enough to convince his critics, but finds that the goal posts have been moved yet again. He has had to pick his way through a maze of imprecise hypotheses, as his critics reply to his specific proposals with a general portmanteau complaint that “these effects could be due to any number of things”. As he himself has observed, the hard-line environmentalist position is not progressive. It does not deign to specify environmental effects in any rigorous way, but tends to multiply ad hoc objections and demand standards never yet achieved in social science. It would be enough to discourage the strongest of constitutions, but despite reverses Rushton pushes on, tracking down weak arguments, studying the implications of research results so as to take them to further levels of examination, gathering new evidence, and as a consequence leaving well-constructed cairns of evidence along the trail-ways of exploration for other researchers to follow.