Happiness is what many people say they want, and it certainly ranked high in the minds of the authors of the American constitution, which may be a recommendation, or a warning. Centuries later psychologists have joined in the pursuit, swimming into the waters formerly infested by philosophers to make their helpful suggestions: count your blessings, set your expectations low, love your neighbour unless they are married to someone else, take each day as it comes, live for the moment, and never let a fatuous banality remain unrepeated.

As you may detect, from time to time I have tried to take a positive view of life, but felt too gloomy to carry out all the uplifting exercises with the required conscientiousness. Perhaps, other than having a tragic sentiment towards life as Miguel de Unamuno so aptly decribed it, I was aware from Lykken’s work that happiness levels have a homeostatic quality, and tend to oscillate around a personal mean in the long term, the absolute level of which has a genetic component.

It was with gloomy interest that I came across a paper which has tracked happiness estimates long term, and linked them with other personal characteristics such as personality and intelligence.

In “Why is intelligence associated with stability of happiness” British Journal of Psychology (2014) 105, 316-337 Satoshi Kanazawa looked at life course variability in happiness in the National Child Development Study over 18 years.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/doi/10.1111/bjop.12039/abstract

In the National Child Development Study, life-course variability in happiness over 18 years was significantly negatively associated with its mean level (happier individuals were more stable in their happiness, and it was not due to the ceiling effect), as well as childhood general intelligence and all Big Five personality factors (except for Agreeableness). In a multiple regression analysis, childhood general intelligence was the strongest predictor of life-course variability in life satisfaction, stronger than all Big Five personality factors, including Emotional stability. More intelligent individuals were significantly more stable in their happiness, and it was not entirely because: (1) they were more educated and wealthier (even though they were); (2) they were healthier (even though they were); (3) they were more stable in their marital status (even though they were); (4) they were happier (even though they were); (5) they were better able to assess their own happiness accurately (even though they were); or (6) they were better able to recall their previous responses more accurately or they were more honest in their survey responses (even though they were both). While I could exclude all of these alternative explanations, it ultimately remained unclear why more intelligent individuals were more stable in their happiness.

Kanazawa reviews the literature, and sets out some expectations: Childhood general intelligence is significantly positively associated with education and earnings; more intelligent individuals on average achieve greater education and earn more money. Intelligence [low] also predicts negative life events, such as accidents, injuries, and unemployment. If more intelligent individuals exercise greater control over their life circumstances, because their resources protect them from unexpected external shocks in their environment, then we would expect more intelligent, more educated and wealthier individuals to experience less variability in their subjective well-being over time. Studies in positive psychology generally show that individuals return to their baseline ‘happiness set point’ after major life events, both positive and negative. So, if less intelligent, and thus less educated and wealthy, individuals experience more negative life events, which temporarily lower their subjective well-being before they return to their baseline ‘happiness set points’, then they are expected to have greater life-course variability in happiness.

Intelligence is associated with health and longevity, and more intelligent children on average tend to live longer and healthier lives than less intelligent children, although it is not known why. Health is significantly associated with psychological well-being. So, it is possible that more intelligent individuals are more stable in their happiness over time because they are more likely to remain constantly healthy than less intelligent individuals.

The National Child Development Study (NCDS) is a large-scale prospectively longitudinal study, which has followed British respondents since birth for more than half a century. Look on this work, ye mighty, and weep. If you want a monument to these island people, look no further. For no other purpose than wanting to know how to give children good lives, all babies (n = 17,419) born in Great Britain (England, Wales, and Scotland) during 03–09 March 1958 were tested, re-interviewed in 1965 (n = 15,496), in 1969 (n = 18,285), in 1974 (n = 14,469), in 1981 (n = 12,537), in 1991 (n = 11,469), in 1999–2000 (n = 11,419), in 2004–2005 (n = 9,534), and in 2008–2009 by which time they were age 50–51 (n = 9,790). If you want this level of intellectual curiosity and altruistic concern for others, avoid caliphates.

The NCDS has one of the strongest measures of childhood general intelligence of all large-scale surveys. The respondents took multiple intelligence tests at Ages 7, 11, and 16. At 7, they took four cognitive tests (Copying Designs, Draw-a-Man, Southgate Group Reading, and Problem Arithmetic). At 11, they took five cognitive tests (Verbal General Ability, Nonverbal General Ability, Reading Comprehension, Mathematical, and Copying Designs). At 16, they took two cognitive tests (Reading Comprehension and Mathematical Comprehension).

Kanazawa did a factor analysis at each age to compute their general intelligence. All cognitive test scores at each age loaded only on one latent factor, with reasonably high factor loadings (Age 7: Copying Designs = .67, Draw-a-Man = .70, Southgate Group Reading = .78, and Problem Arithmetic = .76; Age 11: Verbal General Ability = .92, Nonverbal General Ability = .89, Reading Comprehension = .86, Mathematical = .90, and Copying Designs = .49; Age 16: Reading Comprehension = .91, and Mathematics Comprehension = .91). The latent general intelligence scores at each age were converted into the standard IQ metric, with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Then, he performed a second-order factor analysis with the IQ scores at three different ages to compute the overall childhood general intelligence score. The three IQ scores loaded only on one latent factor with very high factor loadings (Age 7 = .87; Age 11 = .95; Age 16 = .92). He used the childhood general intelligence score in the standard IQ metric as the main independent variable in his analyses of the life-course variability in subjective well-being.

Incidentally, it is a general rule that all cognitive tests load on a common factor. They do not have to do so. It’s just the way the results come out. The Big Five Personality Factors were only measured at age 51. Psychologists hadn’t got themselves sufficiently together on the factor analysis of personality 50 years ago when the surveys started. Anyway, personality doesn’t change all that much over the life course.

Questionnaire reports about life satisfaction can be unreliable, but the long term survey has an internal check: respondent had been asked how satisfied with life they expected to be in 10 years time, and that estimate could be compared with their actual reports a decade later. Kanazawa found that more intelligent individuals appeared to be slightly better able to predict their future level of happiness than less intelligent individuals. He used the prediction inaccuracies at ages 33 and 42 as proxy measures of the respondent's ability to assess their own current level of subjective well-being accurately. Interestingly, more intelligent NCDS respondents were simultaneously more accurate in their recall and more honest in their responses, assessed by looking at another question about how tall they were, their accuracy and honesty calculated when their heights were actually measured in a later sweep of the survey.

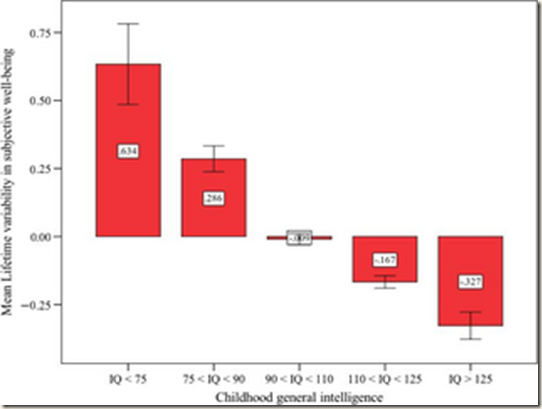

Now to the results. The first point to make, cautiously, is that since this is an excellent, totally representative, large population sample, even small effects will be detected. The figure below shows the effect of intelligence in reducing happiness variability, and that is dramatic enough. The two extreme categories of childhood general intelligence – those with IQs below 75 and those with IQs above 125 – were separated by nearly one full standard deviation in the life-course variability in life satisfaction. However, many of the overall correlations are relatively small.

Although childhood intelligence is the best predictor of happiness, Kanazawa says he does not know why. This is true in terms of the data set, and represents the restraint expected of a researcher. However, as a mere commentator I am allowed to speculate. Given the angry criticism some people have shown Nicholas Wade for speculating about the role of genetics in the development of different societies, this may seem a very hazardous enterprise. Nonetheless, here is my speculation. Intelligence is a resource, and intelligent people know it. They may feel they will be able to overcome problems, or at the very least work round them because of their higher level of ability. This gives them the equivalent of money in the bank, available to deal with a rainy day. So, every reverse can be seen for what it is: a nuisance, not a tragedy. The less able have less in the bank. They cannot dampen down the oscillations in mood brought about by adversity. They meet the big waves in a smaller boat, and have a rougher passage.

Can this speculation be tested? It would predict that all life reverses would be overcome more quickly by intelligent persons, with the possible exception of losing a intellectually demanding job, which would damage their sense of intellectual capital. It should predict a lower rate of suicide, which is against the current findings. I may need to work on this speculation a little further.

Note: Marty Seligman was not harmed in the writing of this post.